History is about people and the decisions they make. It’s Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb, it’s Caesar’s decision to cross the Rubicon, it’s George Lucas’ decision to pen Star Wars — and choosing to direct its prequels — and it’s Steve Jobs’ decision to return to Apple.

History: things that people made happen.

In video-game world, it’s Sakaguchi working on Final Fantasy as a side project in 1987. It’s Kojima sidelining his gruff-voiced protagonist for his seminal sequel in 2001. It’s Ken Kutaragi putting eight cores in the Cell processor in 2004 — and all the ensuing development headaches that came with it. The most fascinating parts of the history of our beloved medium, then, are the idiosyncrasies and eccentricities of its fabled creators and how they drove the decisions they made.

A childhood memory, the death of a loved one, an obsessive passion — these people’s creative processes draw from collective years, centuries, millennia of personal experience and countless cultural influences. Each of these decisions was made by human beings, each with their own unique stewing pot from which brilliance and history emerge.

Miyamoto brings with him his memories of the forests of Japan — the open world of The Legend of Zelda. Kojima brings with him love of film and cinema — Escape from New York was the source of Snake’s namesake. Elden Ring’s Hidetaka Miyazaki draws influence from the tentacles and terrors of Lovecraft, which seemingly slithered their way into the 2014’s Bloodborne. An algorithm, though, brings with its love of nothing and its memory of everything. It didn’t suffer loss nor pain nor love nor angst. Those magical, breakthrough moments behind the scenes — only a handful of which we’ll ever really know about — are stored in the collective memories of developers of decades past. Those late nights, those early mornings, those had-to-be there stories from some of the most creative and talented people in the history of the world.

It’s about those moments, and the moments that almost nearly happened. Final Fantasy was as distinguished from Dragon Quest on its concept art as it is on anything found on their respective cartridges. Those artists could’ve been someone else — decisions were made. Those fascinating junctures in history, from macro decisions about which platform to release a game on to micro decisions as to what colour someone’s gi should be in Street Fighter, were made by people.

That sounds obvious, of course — nothing else could make those decisions back then. But feeling the need to make that distinction shows how profoundly times have changed because something else other than a flesh-and-blood human being can make those decisions.

My point: there’s a story behind every story and I don’t want those stories to be reduced to prompts into a machine. I don’t want those decisions to be made by a machine. My fear is that so-called artificial intelligence will diminish the need and importance of those decisions and the stories they’re part of, that a choice to draw or design something a certain way will be forever erased. AI is a stewing pot, sure, but one driven by algebra and algorithms. It doesn’t have a message, and it doesn’t have a vision and, you could argue harshly, neither do the people who use it for such ends.

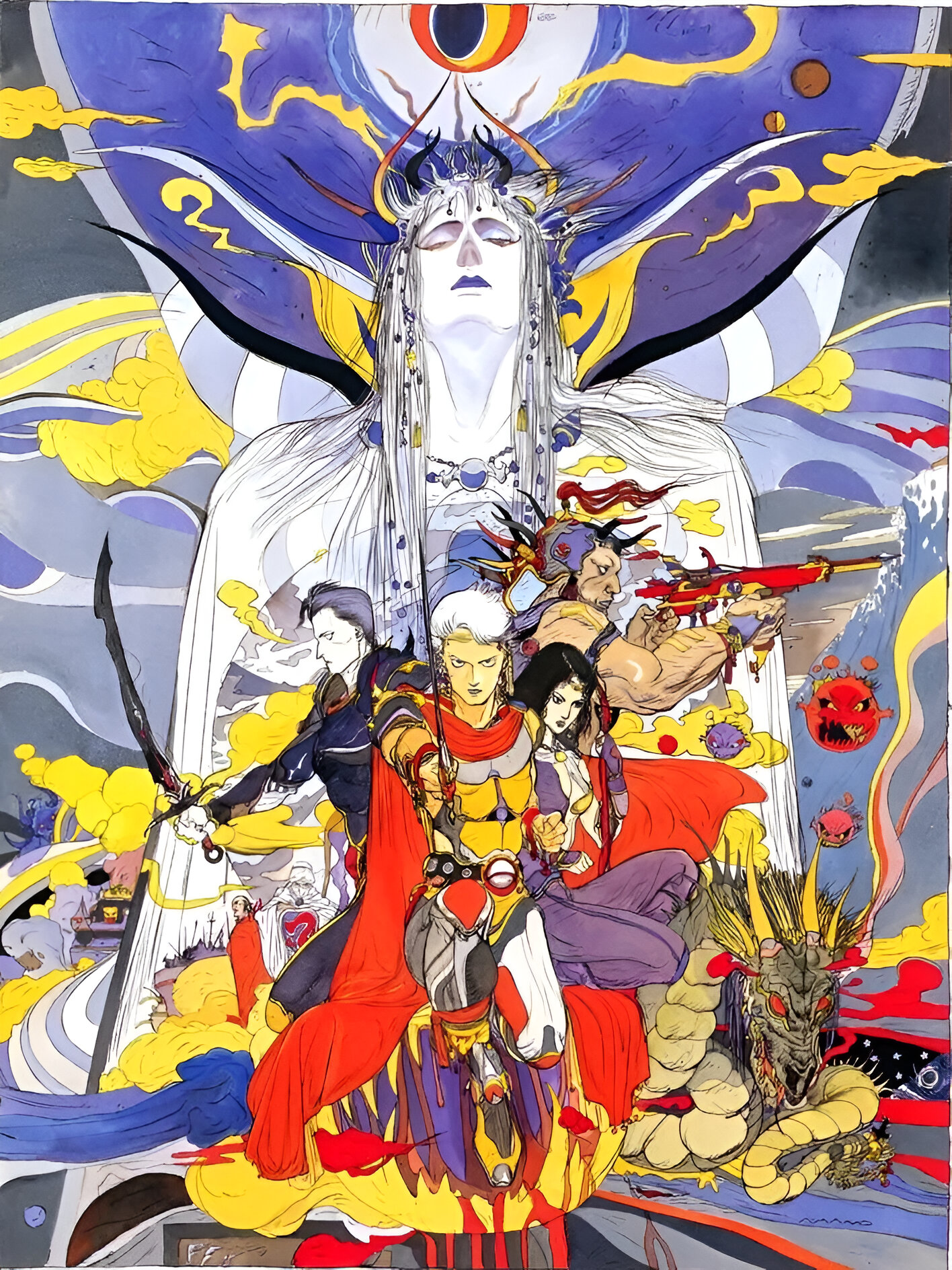

I fear that the Toriyamas and Amanos of the world will be replaced by DALL-E, that the Uematsus and Sugiyamas will be replaced by Suno.

YouTube channels like DidYouKnowGaming are effectively a series of descriptions of decisions people made about video games. Maybe something was named after someone’s favourite food, or maybe someone lost a loved one during development. There’s a non-zero chance that the proliferation of AI in the video-game creative process — or any creative process, really — could mark the end of video game history as we know it because those decisions aren’t made by human beings anymore, not in the way they used to be.

I don’t want video-game history to be relegated to a prompt somebody dropped into a console. I don’t want documentaries talking about how ‘they put it into a model and saw what came out’. I don’t want that story of that decision that was almost made — or made against all odds — to instead be a decision to enter a different prompt or use a different model.

It’s a hyperbolic, tenuous take, admittedly — someone has to decide what goes in and out of these derivation machines, and how and where its output is used. But again, there’s a non-zero chance. In a world where development is dominated by so-called artificial intelligence, it’s difficult to imagine marketing leaning into that. It’s difficult to imagine a Bungie ViDoc or a NoClip documentary where creatives wax lyrical about their use of prompt engineering and large language models.

The counterargument to this historical apocalypse says that AI is a simply a tool, and the human decision-making remains at the steering wheel.

But does anyone want content generated by AI? Valve now requires developers to disclose their use of AI — to a limited extent — on a game’s Steam page and curators are creating collections of games that use AI to empower purchases to boycott games that do so. It suggests that here’s something that feels distinctly icky about the use of AI. I’d argue that it’s because it implies redundancy of the people who would’ve done the AI’s work before, and that consuming such content is a roadmap for our own eventual redundancy. The feeling is, perhaps, that for every track composed by an AI, a talented composer could’ve done it in its stead — and better.

But it also feels like a transfer of power, one against the grain of the trend of years past. In some ways, the person on the street will be more empowered than ever to create a game with the help of AI. In others, we’re potentially transferring that skillset to a handful of corporate masters who control the tools that emulate that same skillset. Right now, developers — indie and otherwise — have knowledge to make something special without those tools. In decades to come, that trajectory isn’t so clear.

Or perhaps taking a stance on AI in video game development isn’t quite so simple. That independent developer who can’t pen music might be able to get his game over the line because AI did it for him — or with him. It’s practically magic, tapping it a repository sum of all human knowledge and experience and extracting it or exploiting it, depending on where you stand. If so-called AI can diminish workloads and mitigate crunch and reduce the need for appalling working conditions by allowing developers to do more in the same amount of time, it’s hard to argue that’s a bad thing.

There’s no immediate evidence of this AI apocalypse happening now, and where it’s all going is unclear. Microsoft announced Muse, an AI model intended to help designers ideate and prototype gameplay. What’s to come of this in real, practical terms — on output, on jobs, on the industry — is still unknown. EA CEO Andrew Wilson said the company will lean heavily into AI-driven development — whatever that actually means.

But this whole AI thing feels distinctly unfair on upcoming generations. A decade ago, that would-be composer may have had to compete with other people — now it may have to effectively compete with the collective sum of all human knowledge these models leverage. Which, in itself, has likely been trained on work of the human — again, it’s nuts that I feel the need to make that distinction — composers that came before. In effect, AI is immortalising humanity but nullifying individuals, meaning that space for the people that come after us is taken by our preserved knowledge. That composition job wasn’t taken by John and Jane born in the year 2000, it was effectively taken by a digital clone of Beethoven who was born in 1770.

It’s a brave new world, then. One where only one thing about the future is clear: so-called artificial intelligence is and will become increasingly prevalent in video game development and the development of just about everything else. But while we see how that crazy, Blade Runner-future unfolds, I hope game creators and the people who create about their creations don’t lose sight of the history and what makes it interesting — the developers who made them and their idiosyncrasies and eccentricities.

Leave a Reply